The Book of Awe Project

Awe is a song we hear, listening to owls, vireos and larks, remembering that birds taught human beings to sing.

Wonder becomes curiosity, a recovered knowing we knew in childhood. A slowed down opportunity for amazement.

Wonder opens access to the question words: why, where, what, the merging of science and creativity, an ongoing Renaissance level rebirth of empathy, of interest, of caring, connecting, inventing and solving.

Pine Cone Skirt in Greenwood Cemetery, photo ©Kathleen Sweeney, 2020

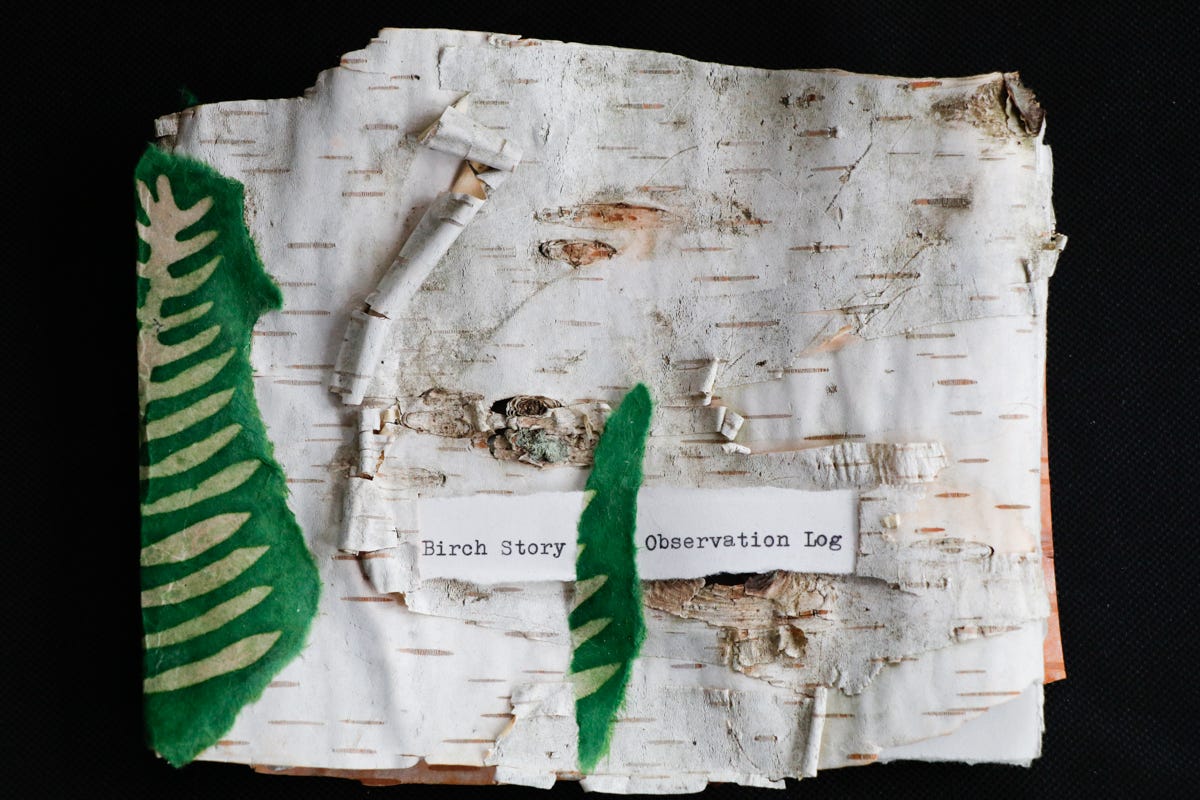

And wow, that root response erupts each time we rediscover fascination for striated silver birch bark, the roving morphology of clouds, the sudden appearance of a bright red amanita mushroom in the grass.

Awe and wonder create expanses of timelessness known to writers, musicians, and artists as the flow state. Recent science has published measurable data on the healing impact of nature walks to reduce stress and enhance our immune systems. Forest bathing, known as shinru yoku, in Japanese, provides the antidote to ecoanxiety by heading to the forests to slow down, look around, and notice.

In states of awe, the breath slows down, and all the senses awaken. This effect is known to Buddhists as open awareness.

The velvet sponginess of the moss, the baked bread scent of autumn leaves, the powdery palimpsest of first frost on oak leaves.

Awe stimulates the Vagus Nerve, and Vagus, in Latin, means wandering. It travels from the brain stem, connecting our respiratory, circulatory, and digestive systems, wandering through our entire bodies. Doctors and psychiatrists are now saying, take a walk in the woods, to relieve trauma, insomnia, depression, stress.

Awe is medicine available to us in the form of wind, of salt air, of bare feet exploring the summer grass.

Birch Observation Log, mixed media, ©Kathleen Sweeney, 2023

Walking in the forest, we meander toward home, to well-being born of belonging, of remembering how to belong to all the elements, listening to celadon laced lichens, cinnamon red maple leaves, thunderous white noise of a waterfall.

Trees predate us by millions of years. Indigenous elders refer to them as relatives. Robin Wall Kimmerer, Native American botanist and the author of the pandemic bestseller Braiding Sweetgrass relates in her native language, that all life forms are referred to as ki, not ‘it’. Ki is genderless, weaving across linguistic miles to find resonance with ‘chi,’ the life force of Eastern philosophy.

The more we examine nature, the more wonder abounds. Deeply observing the bees, frogs, and iridescent dragonflies in our ecosystems, we start to dismantle human exceptionalism, expanding definitions of intelligence. How do the hummingbirds know how to return to the cardinal flowers and bee balm every summer? Why does the sunset ending the day with an ever-changing color array, a never-ending painting?

Awe walks shifts our sense of self with broadened perspective beyond the ego to the wider world around us. We are humbled, we are moved, and moved to become protectors. Surrendering to enchantment transforms us, with an awareness of just how truly small we are underneath the towering oaks.

Awe and wonder experiences become part of our brain patterns, our memorable memories.

Moon jellyfish glowing in the smooth pebbles stepping on the beach at night on Long Island.

Trekking for miles through marshy tundra, to the origin of a red river emanating directly from the Earth in Iceland.

Kayaking under a new moon sky through an inlet in Ireland filled with phosphorescent green glow algae, spirals eddying with each paddle dip.

Stopping on a drive across the Death Valley to an expanse of stars so vast, the jaw drops in wonderment.

A raucous chorus of coyotes piercing the cricket hum in summertime, an exchange of wide-eyed glances around the bonfire.

For just for a moment, we can close our eyes to return to an extraordinary experience of awe. The wind, the white noise of streams, the color spectrums.

On an in breath, we can travel back in timelessness to be transformed. At any time of day.